|

From December 1914, large convoys of Australian troops began departing from the Western Australian town of Albany. They were bound for Egypt and four months of training. In early April 1915, they were moved to the Greek island of Lemnos, only eighty kilometres from Gallipoli. At dusk on 24 April the amphibious invasion began. Troop ships transported the men to within a few hundred metres of their landing site. Around 4 am on the 25th, the first battalions quietly boarded rowing boats and made their way to shore as they had practised at Lemnos. Many in the covering force commented on the unbearable tension. This source gives an indication of the mood of the soldiers:

|

Anzacs at the Great Pyramid |

The first week of the campaign saw an endless number of Anzac attacks and Turkish counter-attacks. Fighting was almost constant and most soldiers were unable to get any real sleep until four or five days after landing. As a growing number of supplies came in to the beach, the Anzacs were ordered to dig in and hold their positions. Already routines were being formed. Private Michael Kirwan wrote home on 10 May saying, ‘Still alive and kicking and having a fairly good time, although they keep you busy dodging lumps of lead Living in dugouts here and beginning to think I am a rabbit.’

At the same time Turkish Commander Mustafa Kemal was demanding of his soldiers, ‘I don’t order you to fight, I order you to die.’ It was going to be a long campaign.

Gallipoli dugouts ©Charles Bean, public domain |

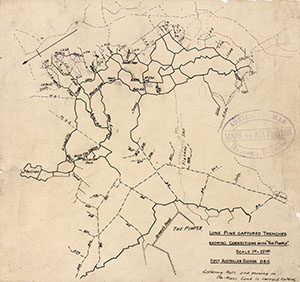

Trenches and tunnels map ©John Stevenson, public domain. |

In little time Anzac Cove was a bustling settlement of thousands of soldiers. Raids, at times heavy and deadly, continued throughout May and June but by July the intensity of the campaign’s first weeks had subsided. Indeed many commented about the boredom and the monotony of day-to-day life on the peninsula. For eight hours on 24 May, a truce was established while troops from both sides buried their dead. Most of the fighting that did take place was in the heights so the area around the beach was relatively safe albeit with the constant danger of Turkish artillery and snipers from above.

A view from above Anzac Cove and its surrounds would have revealed a maze of trenches and tunnels. These lines on the map were so well established they were given names like ‘Seaview Terrace’, ‘Martin Place’ and ‘Cemetery Lane’. Soldiers dug out makeshift ‘homes’ from the sides of the steep hills, which they tried to make as comfortable as possible. The dugouts included their blankets and waterproof sheets for sleep, their limited possessions and maybe a few postcards from home.

|

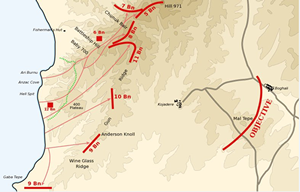

By early August the campaign had stagnated. Following weeks of little activity and widespread cases of dysentery and diarrhoea, the August Offensive was to be the last great attempt to break through the Turkish lines and reach the Dardanelles. The plan involved a three-pronged attack using Australian, New Zealand and British forces. After brief Anzac successes at Lone Pine and Chunuk Bair, the offensive failed.  Lone Pine diorama ©Bidgee, CC BY-SA 3.0 AU |

The August position ©Brass razoo, GNU FDL |

|

On 13 November, Lord Kitchener, Commander in Chief of the British Army paid a visit to the Gallipoli Peninsula. General Ian Hamilton, Commander of the Gallipoli campaign was stood down following the August failures. After reviewing the Allied and Turkish positions, and considering the approaching winter storms, the decision was made to abandon the campaign. Over a number of days, all Allied troops were evacuated without a single death. Their departure was accompanied by a series of decoys and diversionary tactics, designed to hide their intentions from the Turks. The last boats left the peninsula on the night of 19 December. After eight months of fighting, the Anzacs never advanced further than they did on the first day of the campaign. Demonstrate your knowledge of the Gallipoli campaign by completing this timeline activity. Text version (.pdf 43kB) |

Leaving Gallipoli |